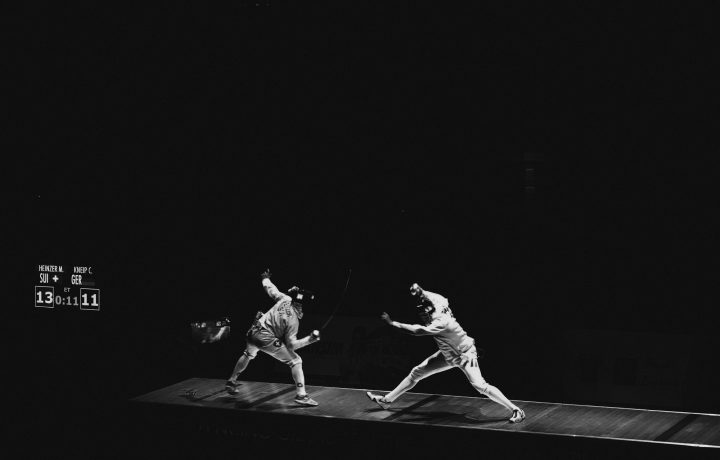

Physical commodity trading is considered to be a highly stressful occupation. Markets are volatile and we need to deal with a number of counterparties at the same time – a real time, in different time zones.

In physical trading – trading and logistics (called very often traffic and/or operations) are inseparably linked.

As a trader you cannot just make a deal and let logistics deal with minutiae of a delivery. In case if any delays happen you will be responsible in front of the client.

Another factor that contributes to the stress level of the profession is the fact that commodities are mostly traded for large distances by the means of marine transportation and everything that concerns the shipping (marine) industry happens in real time and under the impact of factors that we have no control over (weather, being most obvious). Considering volumes involved and sheer scale at which marine vessels operate – any delays and most of mistakes that could be made are by implication very costly and can either kill our profit margin on the deal or even cause losses.

Considering the fact that a role is stressful and details are important, it is not surprising that disputes with counter parts happen on a daily basis.

I would divide all the disputes into:

-post negotiations disagreements

-shipment related disagreements

-quality related disagreements

Categories list is by no means exhaustive, yet representative in terms of “main themes”.

When we negotiate the deal on the phone or by means of email, we generally focus on main points:

-commodity and its specification (quality)

-commodity’s price

-quantity

-delivery basis

-time of shipment

After main points are agreed upon, contracts follow. There is no rule written in stone that buyer signs seller’s contract or seller’s sign buyer’s or that both parties sign each other’s contracts.

The post-negotiation disagreement usually happens when the party receives the actual contract to be signed and starts to voice its objections to its terms & conditions, requesting amendments.

Disagreements at this stage almost never lead to cancellation of the deal.

It is more of the commencement of a fine power play, when each party test how much it can push to secure the contractual details that may decrease their risk or secure stronger position if the deal happens to end up in further disputes.

Buyers can push for original documents/certificates from independent third parties, instead of documents issued by a seller.

COA (Certificate of Analysis) – to put on the contract that it needs to be issued by independent testing company (SGS, Intertek, Bureau Veritas just to name a few) or by the original producer of the commodity – not a trading company.

COO (Certificate of Origin) – to be issued by a Chamber of Commerce not by a trading company.

I think rationale for demanding third party documents is self-evident.

Buyers can also push for actual specs to be put on the contract instead of the standard specs. If actual specs are by no means available, they may push for sampling and analysis of the commodity at the seller’s cost. If you do not know the difference between standard and actual spec please refer to this article for explanation.

If you agree for additional costs, (maybe ask inspection company, for quotation first?), a buyer may push for a place of sampling that would be lowest risk for him.

So, he may want you to put on the contract that samples will be taken after unloading, at the final destination (plant/warehouse) or at the destination port. As a general rule the further down the value chain the sample will be taken the highest risk it poses to you as a seller. Especially if we deal with commodities which are easily perishable (agri-commodities) or easily contaminated (oil and oil products). The concerns are not only limited to adverse changes within spec parameters but also extend to possible weight differences that may arise due to losses during transportation.

Shipment related disagreements happen at later stage.

Buyer might be not happy with BL that you send them. This is why it is crucial to always send the draft of BL by email to the buyer first and ask for explicit acceptance in writing.

Here you are acting under tight time constraints – shipping company will send you a draft of BL for quick acceptance. You need to go to your buyer and get his acceptance first, before reverting to shipping company.

Then if you are on the buying side, your seller may delay the shipment. Numerous excuses can be made, and they may be legitimate or made up. For instance, if a contract was made long time ago at certain price level and since then prices for the commodity shoot up. So maybe now for unscrupulous trader it makes more sense to ship the batch of commodity reserved for you to a buyer who pays much higher price and serve you only later on.

But then, delays might be due to factors beyond seller’s control – problems on the technology side, delaying productions, all sorts of congestions and bottle necks in logistics. If you asked for inspection before loading/on board of the vessel, maybe there is a problem to organize it on time. Maybe customs officials are delaying the shipment due to some deficiencies in documentation? Reasons for delay could be truly varied.

It is less of a problem if you buy a commodity, with an intention of taking a physical position (you basically want to store it and wait for price increase, so maybe a delay can even save you some storage costs). But what if you need this commodity badly for a back to back trade? What if you already sold it and need it to cover your contractual obligations?

Then obviously you are chased and under pressure from your client and you are being treated by your buyer as a party who is not delivering under the contract.

Obviously, you try to mediate such situation for as long as it takes. Usually being transparent on the fact that the producer/another supplier delays a delivery, can get you some amount of understanding. Yet it does not take away a contractual commitment from you.

So as a last resort sometimes you need to buy a material on the spot market to deliver and then either cancel the contract under non-delivery or find new consumer for late material.

In case of the situation when you were forced to buy from the market due to your supplier non-delivery at the higher price, you can try to make your supplier bear the price difference either through arbitration or legal action.

Quality related disagreements usually comes down to specs’ parameters differences in between contracts and results of the actual tests.

In such situation either the party agrees to pay penalty for not delivering the contractual quality or agrees to re-deliver another batch where hopefully tests will come positive.

Paying penalty is usually a better option for a party at fault, since costs of penalty will be usually lower than transportation costs of re-delivery and bringing faulty batch “back home”.

The third option is to disagree with results of the test and agree on commissioning another test by another surveyor or same surveyor yet in different testing centre. In that case traders assign a third-party testing company which they both recognize to perform the tests. The party who will bear the costs of testing would be generally the one who’s previous test results/specification is further away in terms of deviation from the results of final test. Obviously here the agreement need to be reached and careful consideration placed on decisions as:

-whether the same samples should be send for testing

-if the new samples will be send who will take it and where (testing company can do the sampling – but it increases the cost substantially if they need to travel to remote location).

The process should be as transparent as possible with both counterparties equally well informed (buyer and seller on CC: et cetera).

If you would like to learn more about physical commodities trading please join our course.